The United Kingdom

Welcome to the world of Palaeontology in the United Kingdom...

A brief history of British dinosaur discoveries...

‘Dinosaur’ and ‘Britain’ are rarely used together in the same sentence, but, if you can excuse the pun, they should really be two words set in stone.

The name ‘dinosaur’, meaning terrible (or fearfully great) lizard in Greek, was created sometime between 1841 and 1842 by the famous scientist, Sir Richard Owen – founder of the Natural History Museum in London. The very first time Owen mentioned the word in public was during a meeting in Plymouth on 20 July 1841. Hence, the very concept of dinosaurs is a British ‘invention’.

This name was coined to distinguish the remains of several large-bodied fossil ‘lizards’ discovered in the English countryside during the early 1800s. The very first was Megalosaurus, collected from slate mines in the small village of Stonesfield in Oxfordshire and described in 1824 by the Rev William Buckland. The second was Iguanodon, collected from quarries around Cuckfield in West Sussex and described in 1825 by a country doctor called Gideon Mantell.

And finally, there is the often forgotten Hylaeosaurus, also collected near Cuckfield and described in 1833, also by Mantell. Although these large ‘lizards’ were not identified as dinosaurs at the time, their descriptions represent the first scientific accounts of what can definitively be identified as dinosaurs. It was Owen, who later recognised an important link between these animals and other isolated bones, which helped him to establish the new-found group, Dinosauria. Historically, over 100 different species of dinosaur were described from remains in the British Isles, although today, palaeontologists consider approximately 50 to 60 species as valid. There are roughly 1,500 species of dinosaur known worldwide and the British representatives therefore constitute approximately 4% of all dinosaurs currently known.

The British Isles can boast one of the best dinosaur records from anywhere in the world. Dinosaurian remains have been recorded from rocks of Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous age. From the Isle of Skye to the Isle of Wight, dinosaur remains have been collected from various locations in the British Isles. It is often portrayed that almost all British dinosaurs are known from fragments, perhaps just one or two bones. Yet, some British dinosaurs represent nearly complete to complete skeletons and are arguably among the best known in the world.

Not only are the bones and teeth of dinosaurs recorded, but thousands of footprints have been found, along with fossilised dinosaur faeces, called coprolites. As many British finds were described when the science was only just evolving, this subsequently resulted with many firsts. For example, the very first description of what is now identified as a ‘raptor’ (dromaeosaur) was originally misidentified as a type of lizard in 1854. The specimen is an isolated, partial lower jaw with teeth that was collected on the Isle of Purbeck in Dorset and belongs to the dinosaur, Nuthetes destructor.

A selection of British dinosaurs, drawn to scale. From left to right, Hypsilophodon, Thecodontosaurus, Scelidosaurus, Polacanthus, Eotyrannus, Megalosaurus, Baryonyx, Cetiosaurus, Iguanodon and Pelorosaurus. (Courtesy of Nobumichi Tamura: spinops.blogspot.co.uk.)

During the 1800s, as an indirect result of the industrial revolution, dinosaur bones were discovered throughout Britain. Finds were uncovered through blasting in quarries, exploring deep underground in mines, and even through the creation of railway cuttings and reservoirs.

Numerous dinosaur bones were discovered and ranged from fragments to complete skeletons, some representing one-of-a-kind specimens. Prominent individuals, such as Dr Gideon Mantell – the country doctor, eminent palaeontologist and geologist referred to above, and author of several dinosaur studies (including Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus) – had great relations with quarry owners and would actively visit to examine material that was being collected. Specimens would be given to (or purchased by) Mantell, which resulted in a new discovery recorded. Such specimens were subsequently donated, sold or later bequeathed to museums.

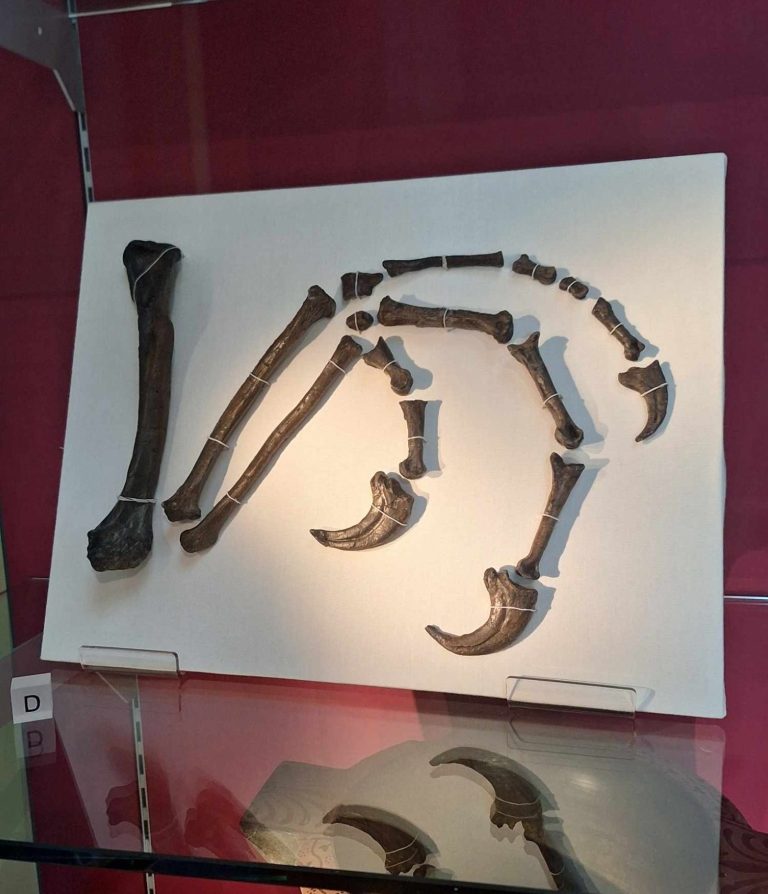

Dromaeosaurus

Dromaeosaurus is a genus of dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period, sometime between 80 and 69 million years ago, in Alberta, Canada and the western United States.

Its fossils were unearthed in the Hell Creek Formation, Horseshoe Canyon Formation and Dinosaur Park Formation. Teeth attributed to this genus have been found in the Prince Creek Formation.

Even though Dromaeosauridae translates from Greek to mean “running lizard,” certain factors indicate their behaviour was much more bird-like. For example, their feet and legs resemble modern birds like eagles and hawks. As such, their body makeup helped aid theories that dinosaurs are more closely related to birds than previously hypothesized.

Although the Dromaeosaurus had flashy killing claws to assist them, they depended more on their crushing jaws to kill their prey. In fact, they had quite a ferocious bite for their size. Their bite was stronger than the Velociraptor despite being nearly one-third the weight.

These amazing dinosaurs also had a claw with a sickle shape that could quickly render their prey immobile. The Dromaeosaurus was nothing short of a finely-tuned and efficient killing machine.

The cast of the Dromaeosaurus arm bones can be found at Sheffield's Weston Park Museum.

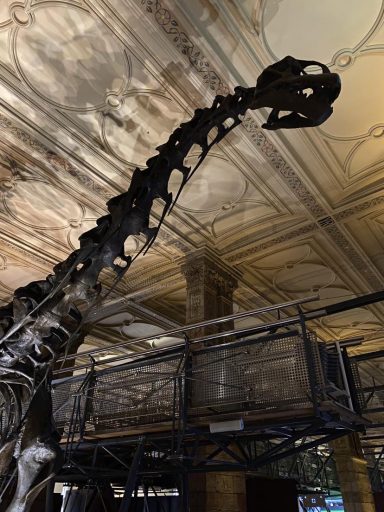

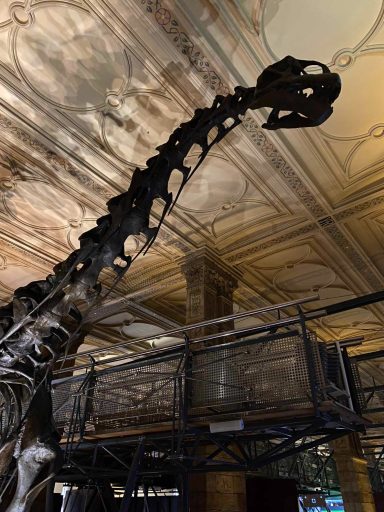

Natural History Museum, London.

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The Natural History Museum's main frontage, however, is on Cromwell Road.

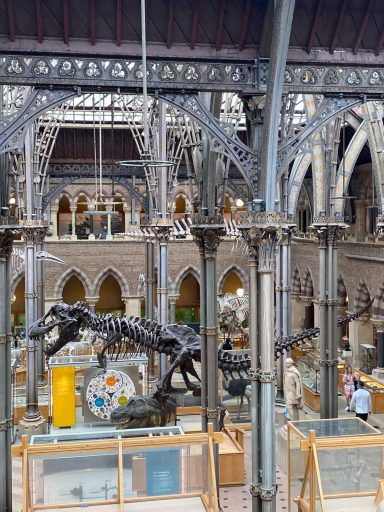

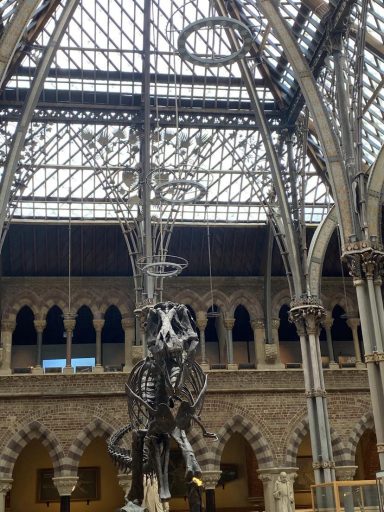

Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It also contains a lecture theatre which is used by the university's chemistry, zoology and mathematics departments. The museum provides the only public access into the adjoining Pitt Rivers Museum

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.